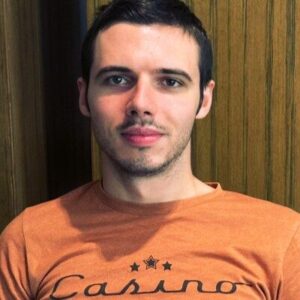

Why should engineers read literature? Why do some self-centered “jerks” still thrive in business? Walt Stinson—American entrepreneur, founder of ListenUp, and a Trustee of the World Academy of Art and Science—shares candid thoughts on self-education, the joy of learning, and crafting one’s life as a work of art.

Stinson calls himself a Renaissance man. He doubts that happiness is an end in itself, praises relentless learning over pedigree, and considers Steve Jobs a brilliant yet egocentric “jerk.” Meet Walt Stinson—an unconventional thinker and a defining figure in U.S. consumer electronics.

From childhood he dreamed of electronics, yet he began with the humanities. He entered the consumer-tech world in the early 1970s, when the field was still taking shape.

In 1972 he launched ListenUp, which has spent five decades designing and deploying audio/video systems and smart-home solutions.

Stinson helped pull together a scattered industry—co-founding PARA, for years North America’s largest alliance of specialty audio makers and dealers—and pushing for the institutions the market needed to mature. In 2009, the Consumer Electronics Association (CEA) inducted him into the Consumer Technology Hall of Fame, an honor for leaders whose creativity, tenacity, and personal drive have advanced the industry and improved lives.

That year, his fellow inductees included Steve Jobs (Apple), Irwin M. Jacobs (Qualcomm), John Shalam (Voxx), and Richard E. Wiley, often called the “father of HDTV.” Today Stinson leads ProSource, a buying group whose members collectively generate about $6 billion in annual revenue.

ProSource’s ecosystem spans managed IT, cybersecurity, enterprise content management, print solutions, digital transformation, and office/industrial equipment. Beyond industry work, Stinson also engages with the U.N. Commission on Human Security.

Leadership begins with breadth

“My humanities background has been invaluable,” Stinson says. Strong speaking and writing gave him an edge—and so did deep technical fluency, rare among executives. “Leaders need expansive thinking. Aim to be a Renaissance person: rounded, curious, conversant across fields, able to weave scattered facts into a coherent view of reality.”

Art remakes us from the inside

Humanities don’t just polish style; they shape values. “Over-specialization shrinks you,” he cautions. He urges his engineers to widen their horizons—visit galleries, read novels, study philosophy. He sees how exposure to the arts slowly alters people’s inner lives—and how much more “art” there is in real-world business choices than outsiders assume. Apple is his favorite example of creativity at the core. At his own firm, they hang paintings on the walls and organize group trips to theatre and concerts.

Schooling can be informal—learning cannot

“Some of the greatest business minds I’ve met taught themselves,” Stinson notes. One acquaintance finished only eight years of school, never attended college, yet became a superb writer and thinker—eventually invited to teach at Yale, the first fellow there without a high-school diploma. “Formal credentials aren’t essential. Serious, continuous learning is. The more you learn, the more you see the size of what you don’t know—and even small steps forward feel thrilling.”

Trust life’s mystery—and grow on all planes

Good teachers can light the fuse, but self-propelled learning must follow. “You can’t lead if learning isn’t a joy,” he says. Real fulfillment also asks for spiritual depth: “Develop mind, body, and spirit—or you cap your potential. If you want to live like a Renaissance person, keep that wholeness in view.”

Happiness is a waypoint, not the destination

“I’ve never treated happiness as my purpose,” Stinson explains. “It’s a signal of whether you’re living well. If you’re unhappy, something’s off.” His aim is ceaseless growth, knowing it can never be fully ‘completed.’ Each day he asks: What did I do to develop? What did I learn about myself—about others? “Lives are like instruments—you can practice until they sing, or settle for noise.”

Competition as a forge

Business, to Stinson, is a training ground. It forces you to solve problems, understand people, communicate clearly, and keep improving. The market gives fast, unblinking feedback—painful at times, but priceless for growth.

Money, success—and difficult personalities

“Money matters—ignore it and you fail,” he says. “But if you chase only money, people won’t follow you or buy from you.” He admits that abrasive personalities can still win: “A self-centered ‘jerk’ can succeed by choosing the right strategy.” He cites Steve Jobs—visionary, obsessive about technology that improved lives, and by many accounts hard on people. “As for me, I won’t pursue success by harming others.”

The art of living is deliberate choice

Jobs also modeled intentionality. “Every decision was on purpose,” Stinson observes. Imitating someone else works only so far; eventually you must choose your own path. There’s rarely a single ‘correct’ option—only choices and their consequences. “When you decide consciously, you become the author of your life’s masterpiece.”

Taming the mind

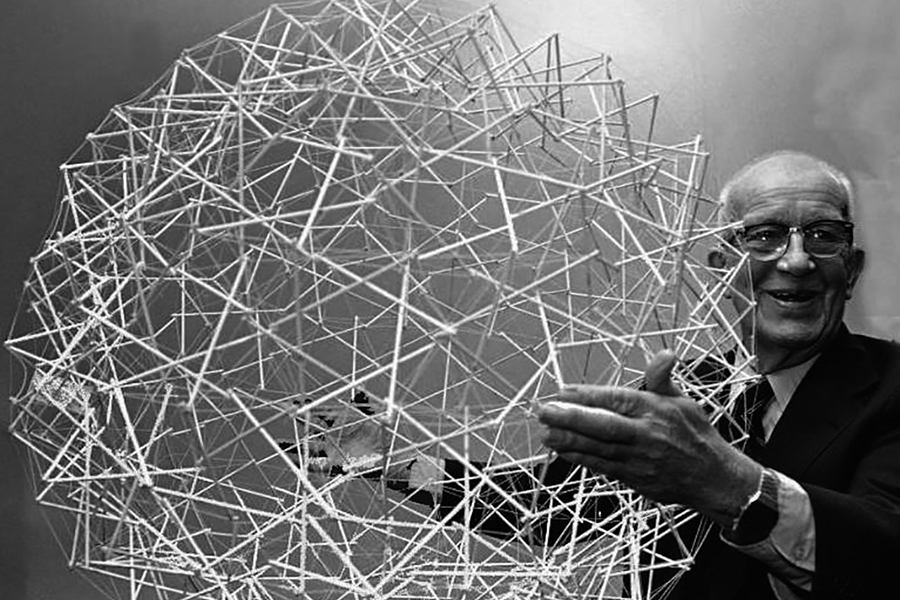

Conscious choice requires a trained mind. “An undisciplined mind is a wild dog,” he says. “Your task is to domesticate it.” He recalls mentor Sidney Harman—the Newsweek owner and audacious innovator—telling him that 95% of people simply drift. Stinson once thought that an exaggeration; with time, he came to agree. “Mastery starts by noticing how many choices we make—and owning each one.”

On Ukraine and the politics of sanctions

Reflecting on U.S. politics, Stinson notes how some populists leveraged anxiety over energy prices to argue against aiding Ukraine—one ripple effect of sanctions. He worries that, if such figures gain power, they could block military support. Similar currents, he says, exist beyond America, where leaders capitalize on price hikes linked to anti-Russian measures.

In his view, sanctions seldom turn populations against their rulers; they often rally around them. For sanctions to bite, he argues, they must be near-universal. As long as major markets—such as India or China—buy Russian energy, he believes the economic pressure will be limited. Only global alignment would deliver decisive impact.