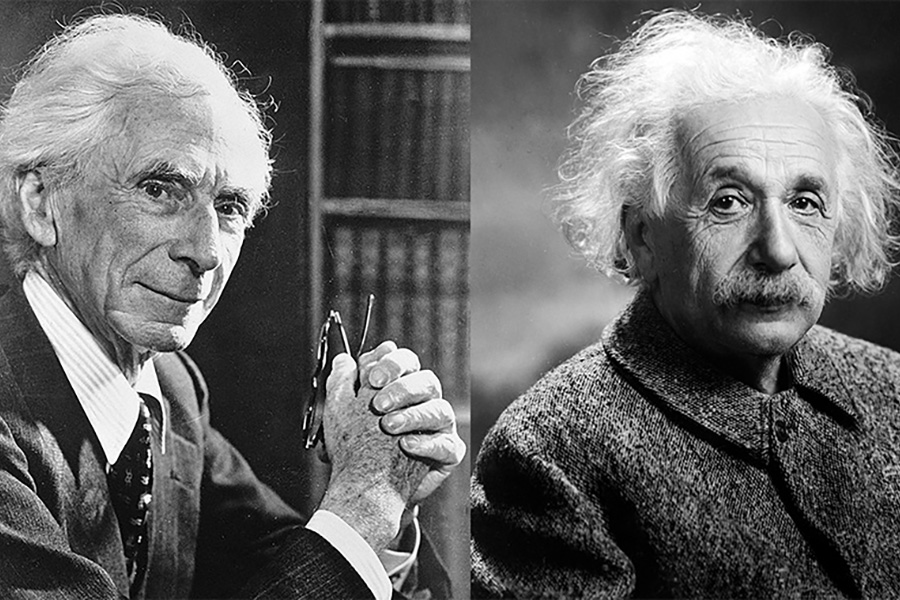

In 1960, as the world still reeled from the atomic age’s promise and peril, a group of scientists and thinkers gathered to form the World Academy of Art and Science. Born from conversations between luminaries like Albert Einstein, Robert Oppenheimer, and Joseph Rotblat, the Academy emerged with a singular purpose: to ensure that humanity’s expanding scientific knowledge served life rather than threatened it.

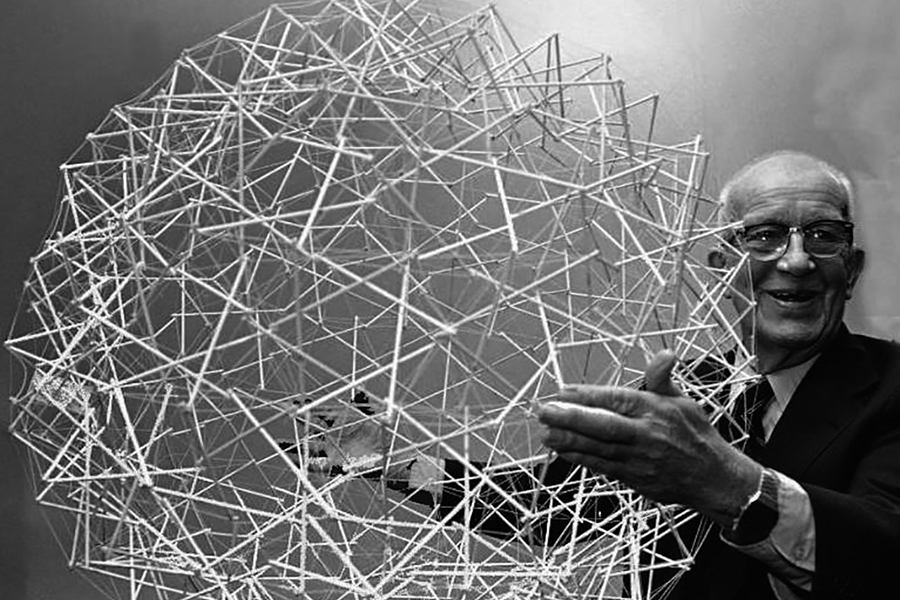

Among those who would join this intellectual fellowship was architect and systems theorist R. Buckminster Fuller, a man whose life’s work seemed almost perfectly designed to embody the Academy’s ideals.

Fuller became a Fellow of the World Academy of Art and Science during a period when both he and the organization were grappling with the same fundamental question: How could human ingenuity solve global problems rather than create them? The Academy was founded on the recognition that scientific discovery had created instruments of unparalleled power for either fulfillment or destruction, and Fuller had spent decades developing what he called “Comprehensive Anticipatory Design Science”—a methodology aimed at making the world work for all humanity through technological innovation guided by ethical principles.

The philosophical alignment between Fuller and the Academy was profound. The World Academy approached all activities from a values-based, human-centered, comprehensive and transdisciplinary perspective, exactly the kind of integrated thinking that Fuller championed throughout his career. Where others saw disciplinary boundaries, Fuller saw patterns and systems. His geodesic domes weren’t merely architectural innovations; they represented a philosophy of doing more with less, of working with nature’s principles rather than against them.

Fuller’s famous concept of “Spaceship Earth”—the idea that our planet is a finite vessel traveling through space with limited resources that must be carefully managed—resonated deeply with the Academy’s mission. The Academy strived to evolve solutions to the world’s pressing challenges by transcending the limits of national self-interest, disciplinary perspectives and conventional thinking while integrating knowledge with universal values and social responsibility. This was precisely what Fuller attempted with initiatives like the World Design Science Decade and his World Game, which he envisioned as a tool for comprehensive resource planning on a planetary scale.

The World Game, launched in 1965, exemplified Fuller’s approach to global problem-solving. According to Fuller, the project was devoted to applying the principles of science to solving the problems of humanity. It was an ambitious simulation that sought to demonstrate how the world’s resources could be distributed to benefit all people, transcending political boundaries and economic systems. Though it remained largely an academic exercise, the World Game represented the kind of transformative thinking the Academy championed—ideas powerful enough to reshape how humanity approached its collective challenges.

What made Fuller an ideal fellow of the World Academy was his refusal to separate technical innovation from moral responsibility. The Academy’s founding motive came from the knowledge that academic knowledge cannot be separated or divorced from the social responsibility of how the knowledge is used. Fuller lived this principle daily, whether designing affordable housing solutions, developing more efficient transportation, or creating his revolutionary Dymaxion Map that portrayed the world without the distortions inherent in traditional projections.

Fuller’s work embodied what the Academy meant by integrating art and science. The inclusion of Art in the title of the Academy was intended to foster a marriage of the objective and subjective dimensions of knowledge essential for understanding consciousness and social evolution. Fuller was simultaneously engineer, architect, philosopher, and poet—a comprehensive thinker who understood that solving humanity’s problems required both technical precision and creative imagination. His geodesic structures were mathematical marvels that also possessed aesthetic beauty and symbolic power, representing possibility and human ingenuity.

The World Academy’s motto, “Leadership in thought that leads to action”, could have been Fuller’s personal creed. He spent over fifty years traveling the world, delivering lectures, writing books, and developing prototypes—always translating ideas into tangible demonstrations of what was possible. He believed passionately in humanity’s capacity to consciously direct its own evolution, to choose cooperation over conflict, abundance over scarcity.

Fuller’s relationship with the World Academy of Art and Science represented more than institutional affiliation. It was a meeting of shared conviction that the great challenges facing humanity—from resource management to environmental degradation to social inequality—could only be addressed through transdisciplinary collaboration grounded in universal human values. Both Fuller and the Academy understood that technical solutions without ethical frameworks were insufficient, and that ethical aspirations without practical implementation were equally hollow.

As the Academy continues its work into the twenty-first century, grappling with challenges Fuller foresaw—climate change, resource depletion, technological disruption—his example remains instructive. He demonstrated that addressing global problems requires thinking comprehensively about systems, acting boldly with prototypes and demonstrations, and maintaining unwavering faith that human creativity, when properly directed, can indeed make the world work for everyone.