When the World Academy of Art and Science (WAAS) was founded in 1960, it was born out of a paradox of the modern age — that human genius could both unlock the atom and threaten the survival of civilization. Among the intellectuals and leaders who helped define the Academy’s purpose was Swedish diplomat, sociologist, and Nobel Peace Prize laureate Alva Myrdal — a woman whose life work embodied the Academy’s founding ideals: to use knowledge not for domination, but for the flourishing of humankind.

Myrdal’s journey from social reformer to one of the world’s leading voices against nuclear proliferation parallels the moral evolution of science itself. As nations rushed to harness the power of the atom in the wake of World War II, Myrdal stood apart — not as a scientist but as a visionary who understood the social and psychological consequences of living under the nuclear shadow. Her intellectual foundation was deeply rooted in the Scandinavian welfare model she helped shape with her husband, economist Gunnar Myrdal. Together, they sought to balance economic growth with social justice — a balance that WAAS would later frame as the search for “science with a conscience.”

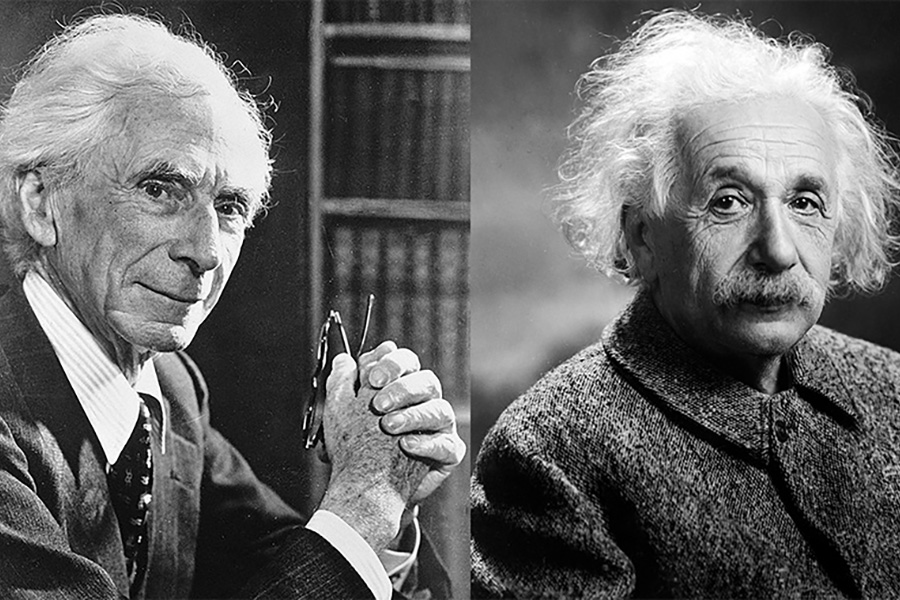

At its birth, WAAS brought together luminaries such as Bertrand Russell, Robert Oppenheimer, and Joseph Needham — individuals haunted by the double-edged legacy of scientific discovery. They shared a conviction that the atomic age demanded a new moral architecture, a framework in which art, science, and human values were inseparable. Myrdal’s commitment to peace and human development made her a natural ally in this mission. Though not a physicist, she possessed the moral clarity that many scientists lacked: an insistence that knowledge carries responsibility.

In the 1950s and 1960s, Myrdal’s focus sharpened on what she called the “immorality of deterrence.” As a diplomat at the United Nations and later Sweden’s Minister for Disarmament, she challenged the orthodoxy that peace could be preserved by the threat of annihilation. In speeches that startled her contemporaries, she dissected the logic of the nuclear arms race: “Security based on fear,” she said, “is the most insecure form of peace imaginable.” Her insistence that true security must be based on cooperation and trust echoed the philosophical core of the World Academy’s founding charter, which warned that humanity’s survival depends on uniting scientific progress with ethical wisdom.

While Oppenheimer and Russell struggled with the moral aftermath of their own scientific achievements, Myrdal offered a practical path forward. Her leadership at the Geneva Disarmament Conference and in the United Nations General Assembly transformed abstract moral principles into diplomatic strategy. She advocated tirelessly for the Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT), pressing both superpowers to accept verifiable limits on their arsenals. Her 1975 Nobel Peace Prize, shared with Mexican diplomat Alfonso García Robles, was not only recognition of her personal courage but an acknowledgment of her ability to transform ethical conviction into institutional change — the very synthesis WAAS was created to achieve.

The Academy’s founding statement declared that “the future of humanity depends upon the wise use of knowledge.” Myrdal’s entire career can be read as a meditation on that sentence. For her, “wise use” meant understanding the social systems that determine how knowledge is applied — whether toward the welfare of people or the destruction of cities. In her early sociological writings, she explored the relationship between family policy, education, and equality, believing that social progress must be designed as consciously as scientific progress. Later, in her disarmament work, she extended that logic to the global stage: if humanity could engineer its welfare systems, it could also engineer peace.

Her intellectual kinship with WAAS extended beyond shared ideals. Both Myrdal and the World Academy viewed art and science as two halves of the same moral project. The arts, they believed, could humanize the abstract power of science; science, in turn, could lend rigor and evidence to humanity’s moral aspirations. In an age when technology was beginning to outpace ethics, Myrdal and WAAS sought a balance — a reconciliation between the analytical and the humane.

It is easy today to forget the radicalism of her stance. In the heat of the Cold War, to question nuclear deterrence was to risk political exile. Yet Myrdal’s voice, steady and unflinching, broke through the noise. She refused to accept that moral choices were subordinate to strategic logic. “The world has not yet learned,” she said in her Nobel lecture, “that security can only be achieved through disarmament and confidence, not through arms and fear.” In those words, one hears the echo of WAAS’s enduring mission — to move the world from competition to cooperation, from fear to wisdom.

Myrdal’s legacy offers a lesson that is as urgent now as it was in 1960. The weapons may have changed — from nuclear arsenals to algorithms and autonomous systems — but the moral dilemma remains the same: how to ensure that human intelligence, amplified by technology, serves the cause of life rather than its destruction. WAAS continues to grapple with this challenge in the age of artificial intelligence and biotechnology, and in doing so, it walks a path Myrdal helped clear.